Kent Familton’s work is rooted in abstraction and the deliberate use of line, space, color and gesture to balance geometric specificity and painterly spontaneity. Glimpses of architectural space and landscape are enmeshed in layers of accumulation and erasure. Raised between the urban sprawl of Los Angeles and the rainforest in Darién, Panama, Familton has developed a nonhierarchical visual language that comfortably resides in the liminal space between extremes. In the interview below he discusses his practice and what art can mean amidst a pandemic and uprisings against police brutality.

LC: Your work is shaped by your environment in surprising and fascinating ways. How have the COVID-19 shutdown and the protests against police brutality affected you?

KF: I am still processing the horror and sadness of all the recent blatant racial injustices and violence against people of color. Having witnessed as a young man the Rodney King beating and LA riots 30 years ago, I am heartened by the overwhelming support for confronting systemic racism. The pandemic has highlighted inequities in this country, proving that the people and places we undervalue as a society are most vulnerable. COVID-19, like racism and climate change, is a social justice issue that is killing our family, friends, and neighbors. But I love this city and I have hope that we will finally do better by each other.

The isolation of the past few months has been a difficult adjustment for me. I grew up with, and still have, a deep connection to every inch of the city and my imagery has always dealt with the interconnectedness of LA: its streets, freeways, neighborhoods, its people. My multicultural upbringing, biracial heritage, and the city itself have bonded me to the community in profound ways that are expressed in my work. Those connections are even more poignant now that we see that we are all linked to one another in a global community.

LC: LA is often thought of as a volatile patchwork of neighborhoods, histories, and geographies: mountains and beaches, freeways and skyscrapers, downtown and Skid Row. The city comes through in your layered marks, your use of collage elements and in your restrained color palate. In many ways, your evocation of place and identity challenges what we expect from abstract art. How did you develop this approach to painting and who were some of your influences along the way?

KF: Our city is much more nuanced than people recognize. It contains all the extremes you mention and many more. However, physically moving through the city from one block to the next provides subtle shifts in sound, smell, and sight; it's a place not rendered in juxtapositions but in harmonious and sometimes dissonant melodies. My desire to convey something through “pictures” slowly and organically became less about representation and more about interpretation and investigation. I became more interested in what wasn’t on the canvas. John McLaughlin and Agnes Martin had a profound impact on the paintings I was making and the things I was thinking about. What did I expect from a painting? What did I learn from the experience? What did it convey, and did it add up?

To skim the surface, some of my other influences have been Jazz pianist Andrew Hill for his accessible, challenging and experimental compositions; Arshile Gorky for his spontaneity and lyricism; Milton Avery for his colors and simplified yet expressive idiom. Molas made by the Kuna women of Panama have always enticed me. I am drawn to their tactility, lines and colors, as well as their ability to tell vastly different stories through combinations of abstraction and representation. It’s not something that I consciously reference, but I often find myself thinking about them after the fact.

LC: Many of those references have in common a balance between structure and spontaneity driving the composition. For instance, Agnes Martin uses gesture as a device that distances expression yet still imparts a sense of place, which is something we've talked about happening in your work. But your mention of Molas suggests that there is a combination of places being referenced, and you've connected your frequent use of gray to concrete both in LA and in the Panama Canal. In other words, color and pattern aren't purely aesthetic but have a social reality that is often contested.

Let's talk about your drawings. While clearly related to your paintings they are also a distinct body of work. How do you think about that relationship?

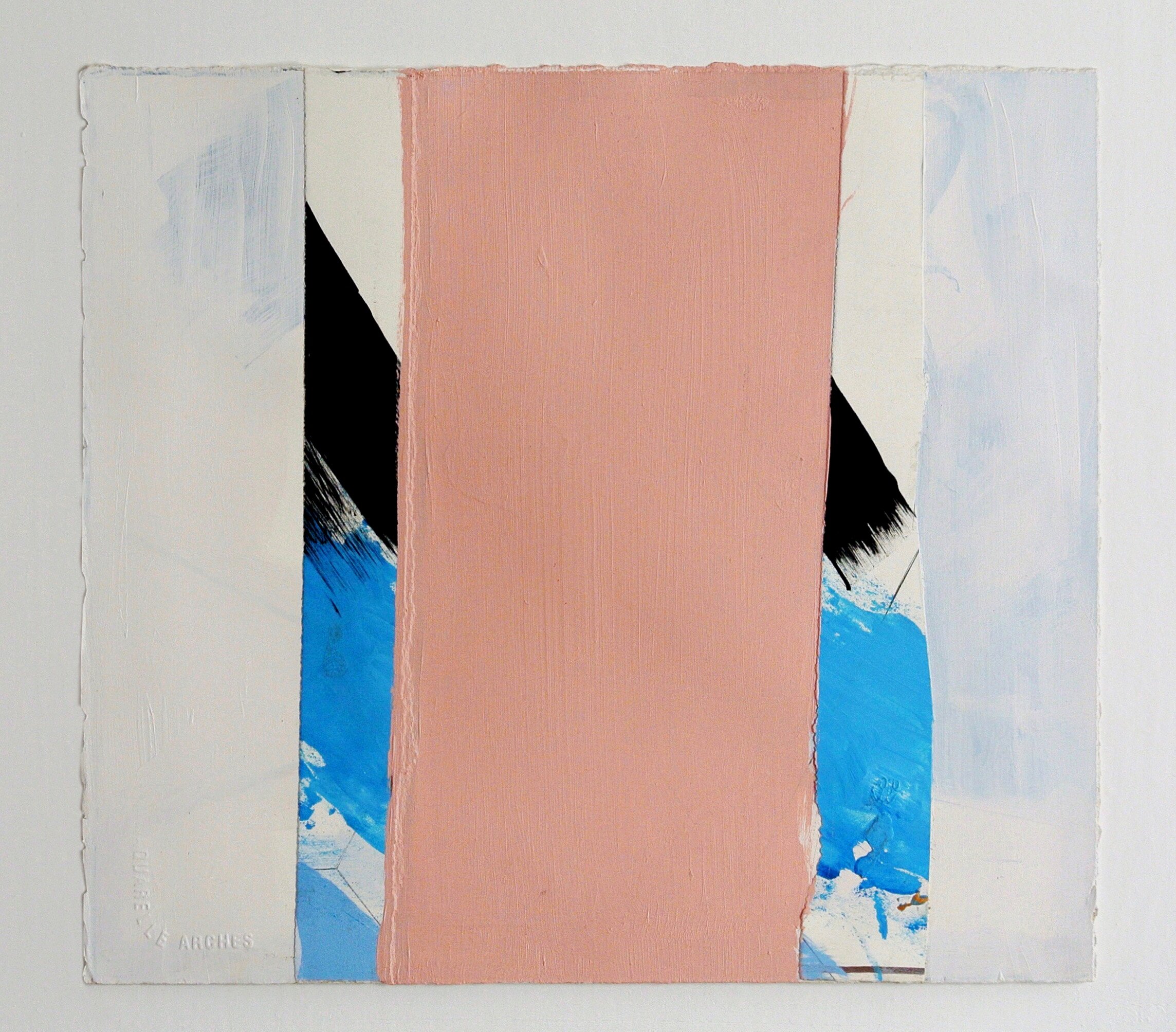

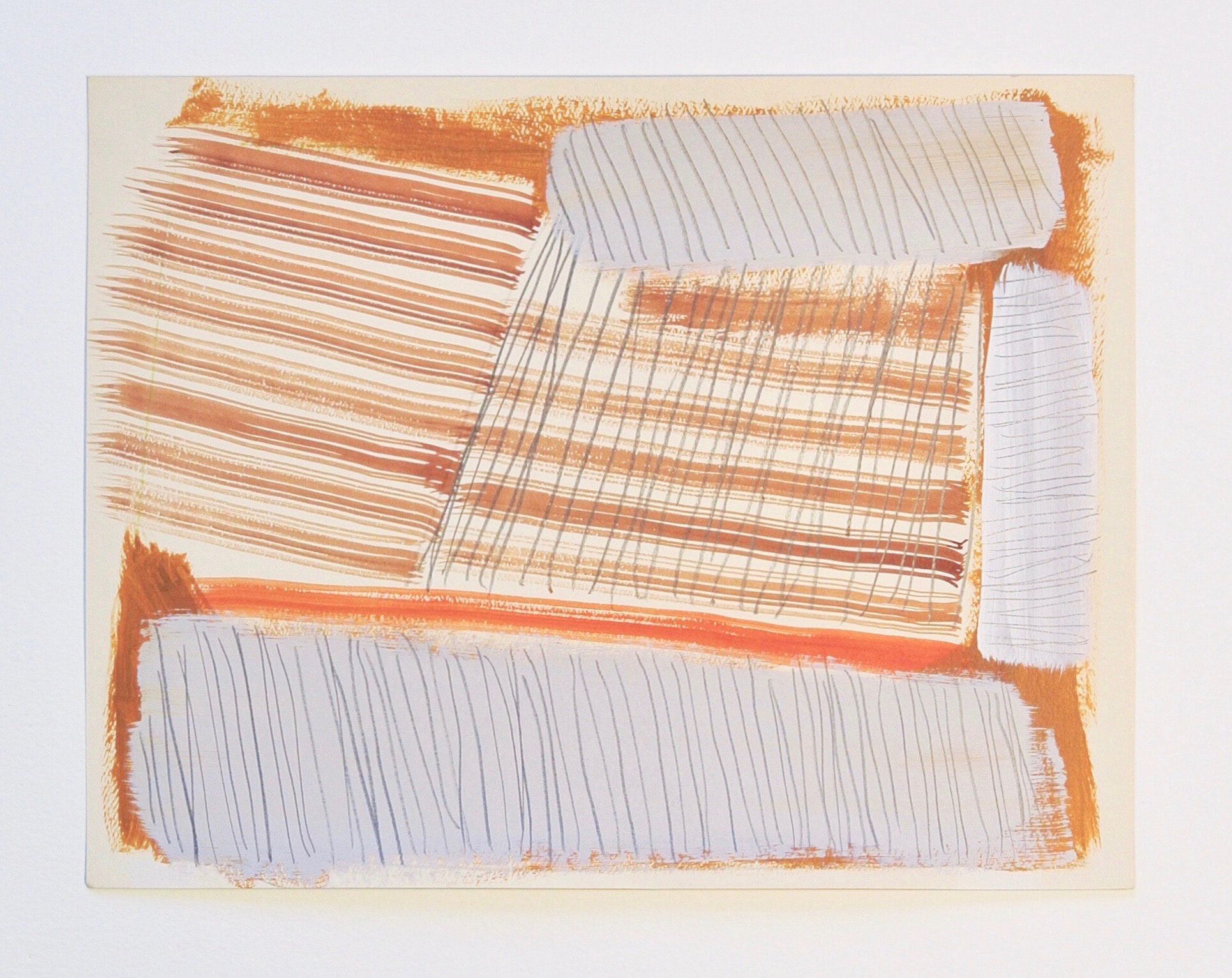

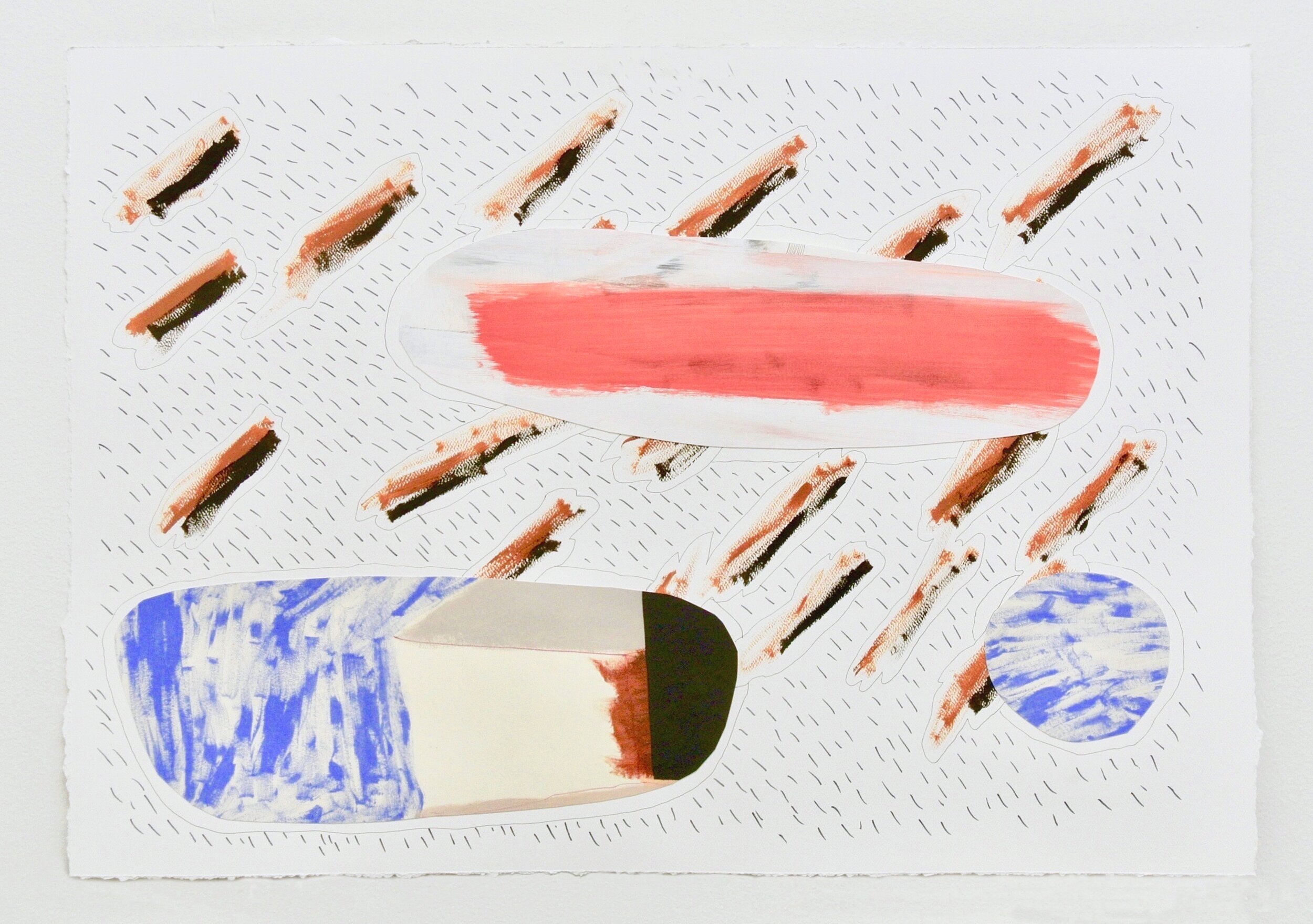

KF: There is a fluidity between them as they share recurring motifs that influence and reverberate with one another. There is always something loose, intimate and open about making a drawing. The scale, materials, and time involved lend themselves to creating in a different way. The expectations are there but the “monumentality” aspect that sometimes accompanies painting is rarely a factor. The drawings never set out to be translations or studies for paintings. They are more direct– less about process, discovery and finality and more about an impulse or feeling. I’m constantly figuring out structure, composition and context in both painting and drawing but there is less dismantling and fussing with the drawings, especially since the paper becomes a ground to exploit rather than obliterate. There is a sense of freedom with mark making on a smaller scale that can get lost in a painting.

LC: I can see the freedom and the incident in your marks but also a thought process that reveals itself over time. The pencil marks and outlines in Adrift, for instance, challenge the viewer to reconstruct the development of the composition. Even though you use acrylic, watercolor, and collage elements these are drawings in a traditional sense in that they provide a direct connection to your material investigation and thinking.

To sum up, it strikes me that the subtlety and layering of your work stands in stark contrast to the blunt spectacle of information we are bombarded with these days and especially during such a tumultuous time. I'm wondering if the current upheaval has changed how you think about your work.

KF: In times like these it would be impossible to not be affected personally and artistically. My work is influenced by my experience and surroundings, so the current crises have absolutely changed the way I think. The editing and filtering that goes into my process is expressed in the immediacy and vulnerability of mark making and erasure in conscious and subconscious ways, starting with a notion of what I want to see, interpret, choose, absorb and ignore amid the chaos. Layering is so much about the history of the hand and material while prioritizing one shape over another, with different degrees of emphasis and opacity.

We have indeed been bombarded with a spectacle of information and stimuli for a long time, and I see my work as both a contrast to it and a sublimation of it. I am also using this time to learn about and examine my own small part within the institutions of art, as an artist and a teacher– to be cognizant of the gravity of this moment as it relates to art. As an artist it is my responsibility to be in conversation with the world outside my studio walls as much as it is my job to speak my own truth. So, it is crucial for me to engage in this moment with an open heart and mind.

Kent Familton holds a BA in Art from UCLA and an MFA from The Claire Trevor School of The Arts, UC Irvine. His work has been exhibited at LA Louver, Bentley Gallery, The Luckman Fine Arts Complex, Monte Vista Projects, LAXART, Autonomie, Torrance Art Museum, d.e.n. Contemporary Art, The Green Gallery East and Andi Campognone Projects. Familton lives and works in Los Angeles.